If you have an iMac and were wondering if a new M1-based Mac would be better for your video-editing workflow, here’s a discussion of the performance of the M1 Mac mini (and by extension, the other M1 Macs) compared to a top-spec iMac from a couple of years ago, mostly talking about Final Cut Pro.

Because blogs have mostly died, I’ll be posting this on Twitter too. A lot of this is based on my YouTube video, but reading the text is probably going to be quicker.

There’s no doubt that the new M1 chips are a huge step up in CPU performance.

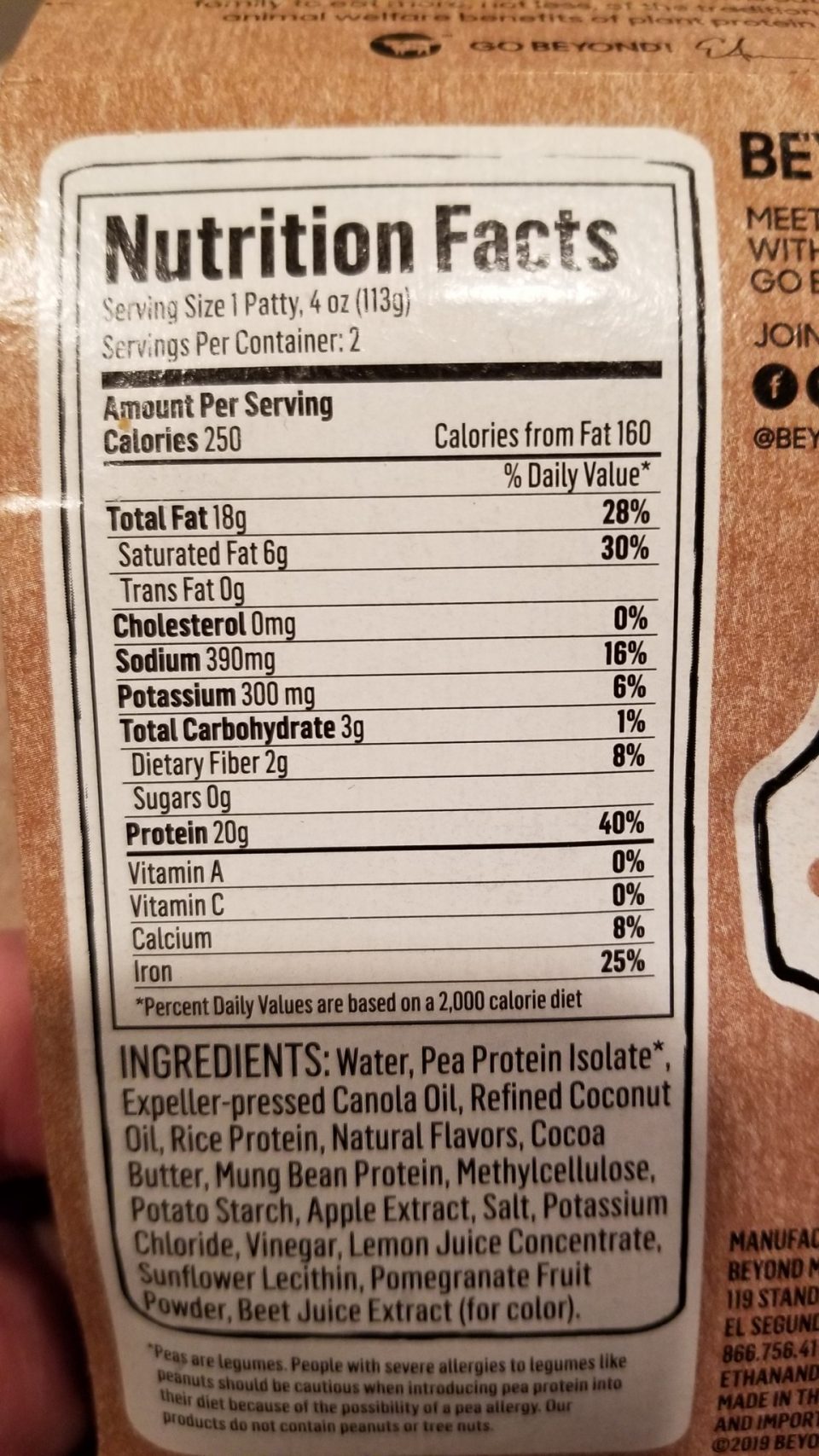

On Geekbench, here’s the gap between my 2017 iMac (4GHz, a crazy 64GB RAM, and a Radeon 580 GPU with 8GB VRAM) and the cheapest M1 Mac mini (8GB RAM). The Metal performance is where the iMac wins, and more modern GPUs can do much better than this.

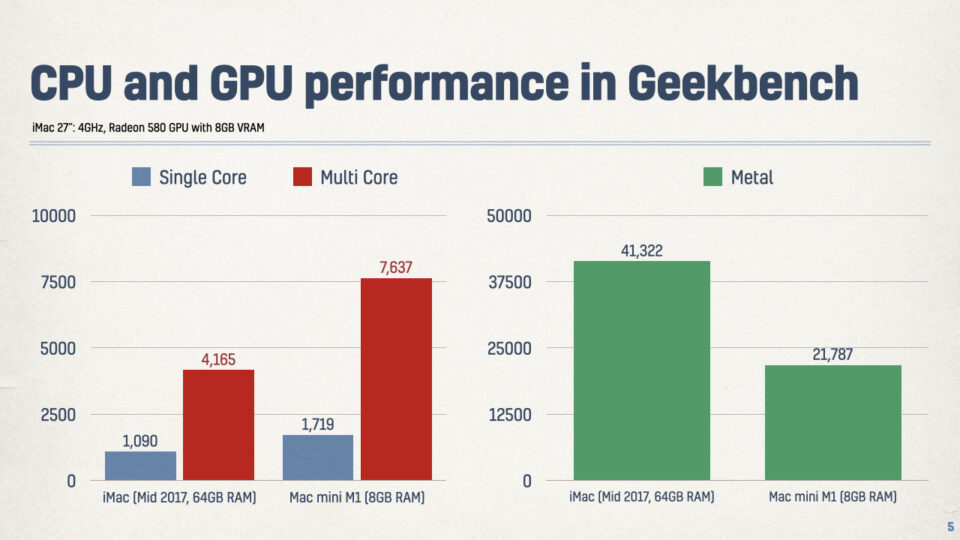

Simple performance tests show a clear win to the M1 Mac mini. Both machines were smooth at playing back 4K H.264 footage, as you’d expect, and the M1 was faster to export. (By the way, I used ChronoX Pro for most of these benchmarks — it’s great.)

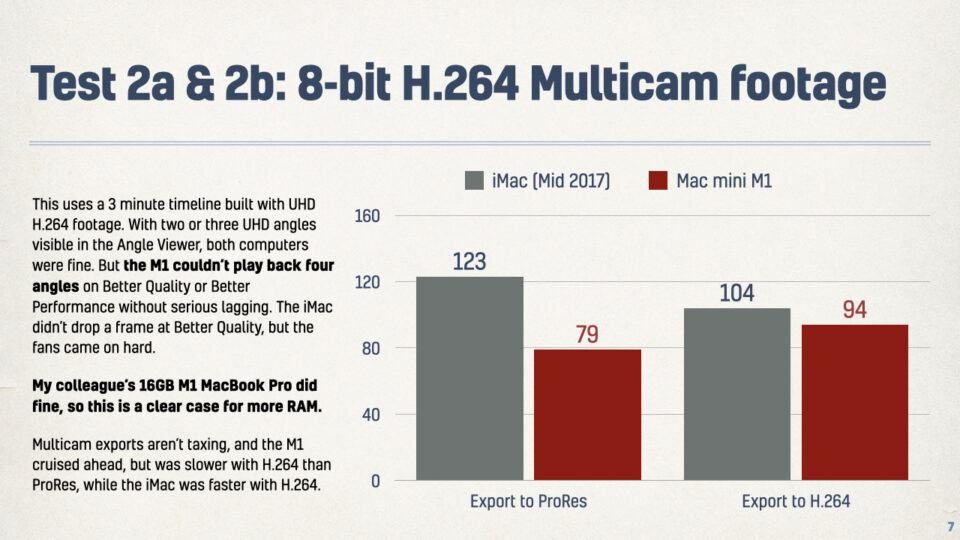

Multicam footage showed the first issue with the M1 Mac mini: a RAM problem. With H.264 footage, the 8GB M1 struggled to show playback of four angles at once, while the iMac was fine, and a 16GB M1 MacBook Pro did fine too. Optimising to ProRes also fixed this.

Modern codecs are a strong point for the M1, and 10-bit H.264 from the GH5 performed much better on the M1 than on the iMac, which has always struggled with these files.

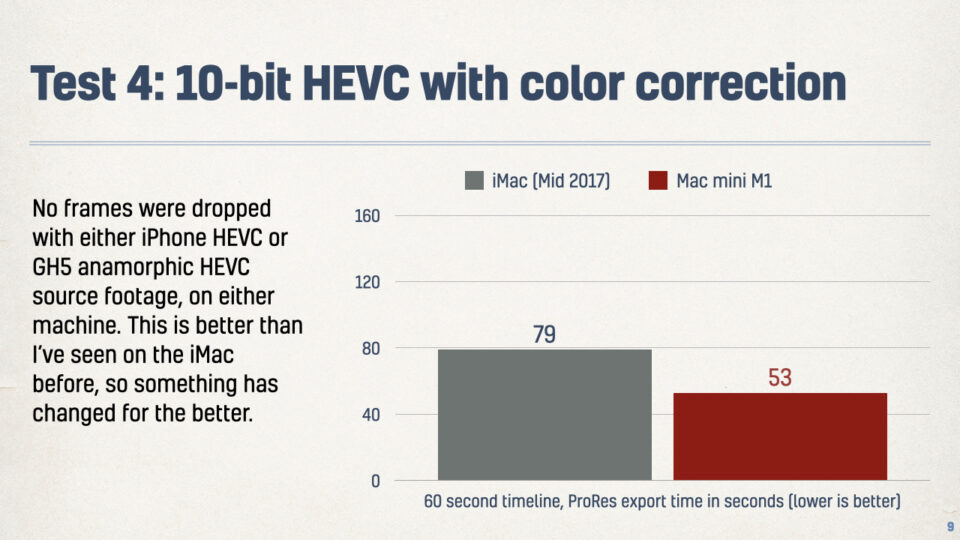

It’s the same story for 10-bit HEVC, from the GH5 and the iPhone 12 Pro:

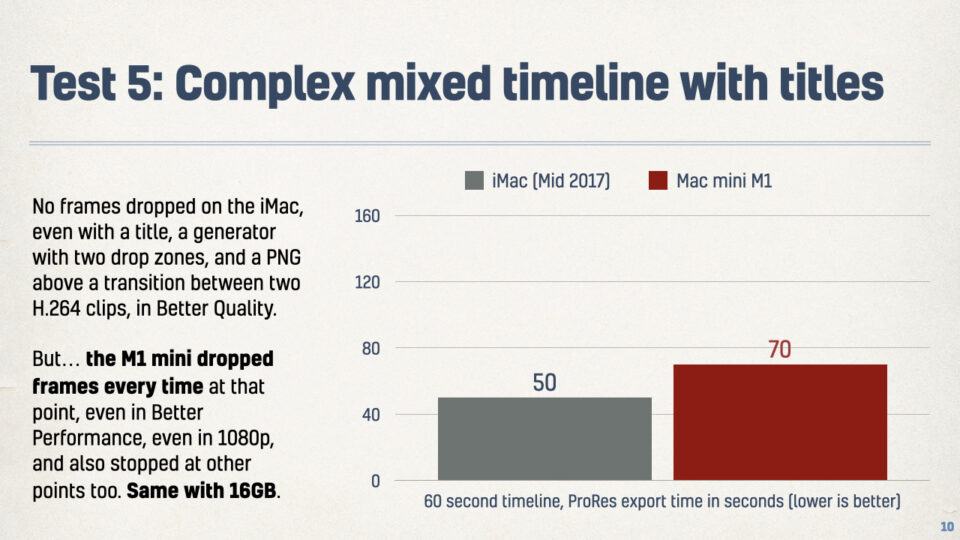

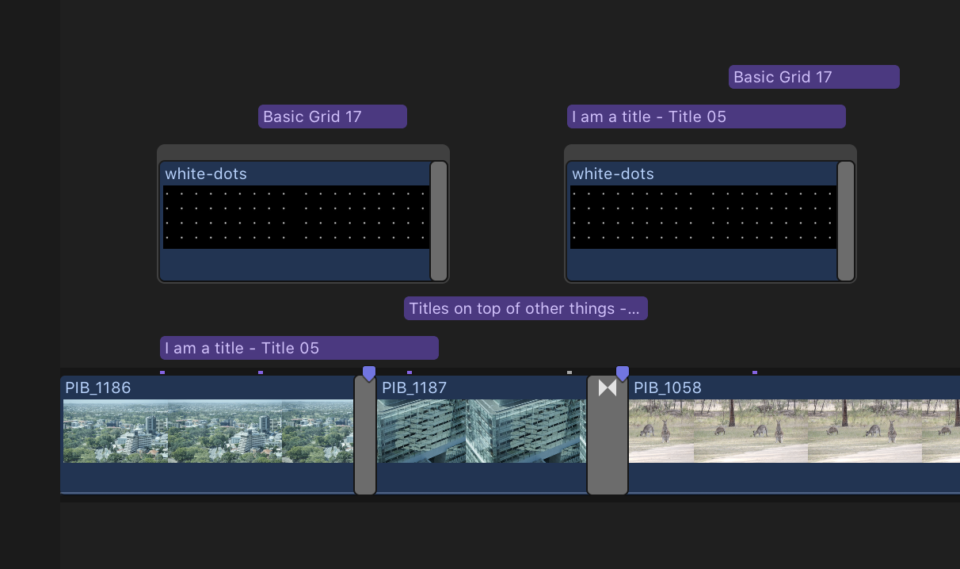

Here’s an issue. When adding a few titles, overlaid graphics, and drop zones with 4K video inside, the M1 dropped frames when the iMac does not, and RAM isn’t the problem. Dropping to Better Performance and dropping the resolution to 1080p didn’t fix it either.

I repeated this GPU-heavy test the next day, and while the iMac was still usually 100%, it *sometimes* dropped a frame or two if under load from other apps. The iMac always did better, but this test is still near the limit of its capability.

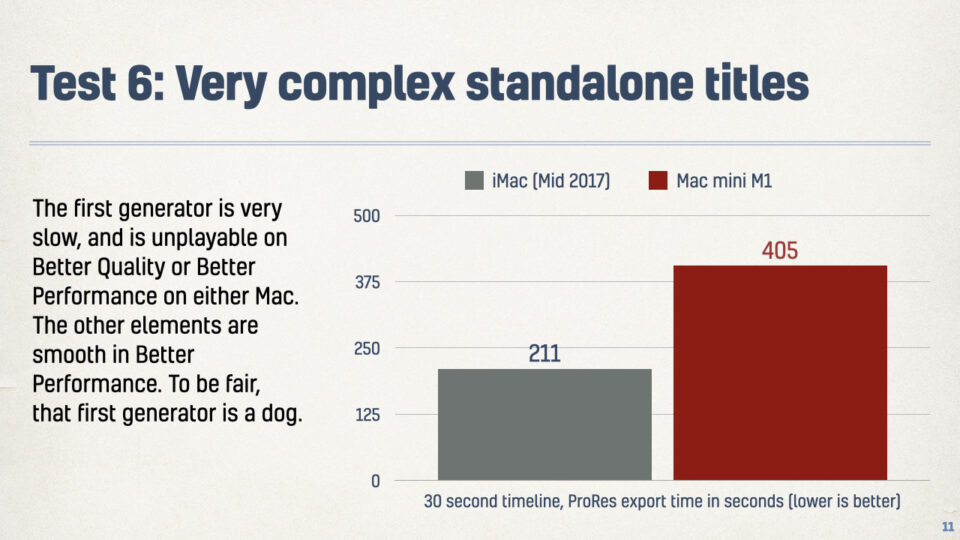

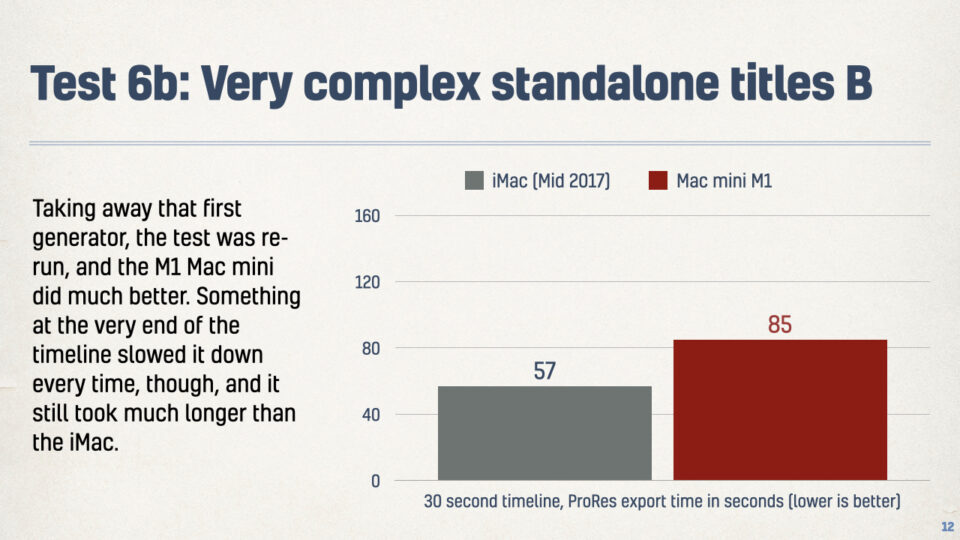

Ramping up to some really complex titles from LenoFX.com and motionVFX.com, the iMac did better than the M1. The very first generator is very slow on both:

…but the iMac won even without it.

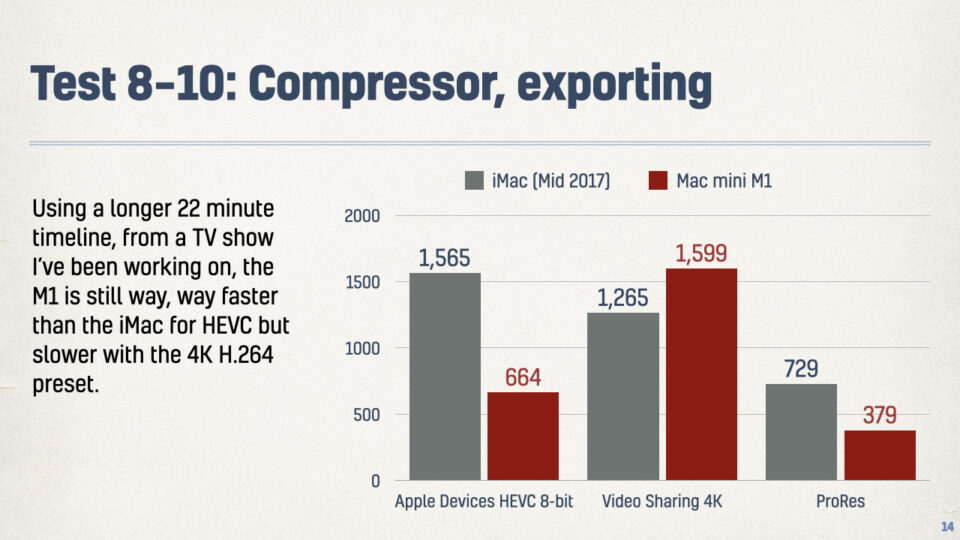

Compressing to 10-bit HEVC via Compressor, with hardware encoding made active on the M1, shows just how much faster that can be. If you need to export a lot of 10-bit HEVC, and you don’t have a Mac with hardware encoding (such as a pre-2020 iMac) then you need one.

Compressing a much longer video (22 minutes, a TV show pilot I’m shopping around without success) showed that the M1 is much better at HEVC and ProRes than it is at H.264, which the iMac was faster at. Sharing services are fine with HEVC, but a client’s random computer? Maybe not.

Handbrake was much much faster on the M1, so perhaps FCP can improve?

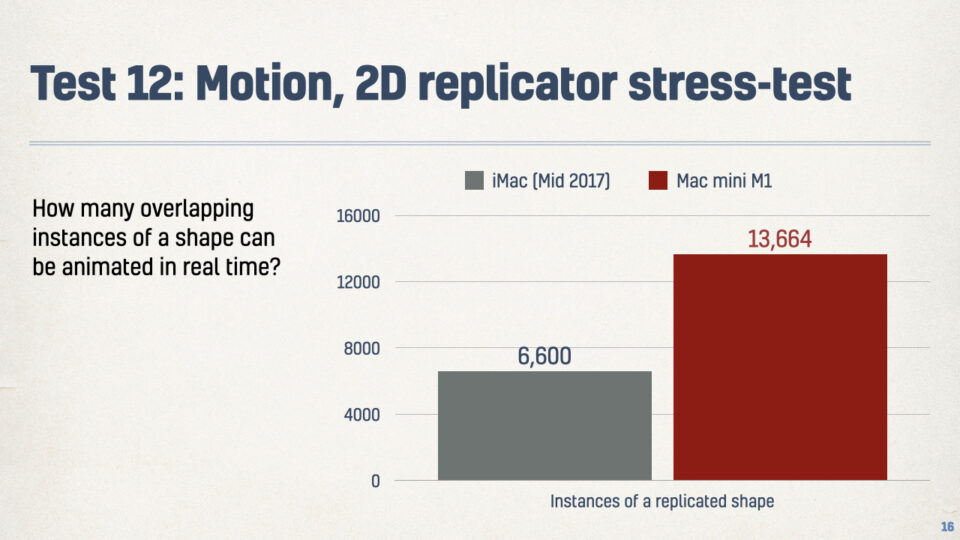

A quick and dirty Motion test, overlapping thousands of animated, replicated shapes, was a clear win to the M1. Many operations in Motion are CPU-bound and not GPU-bound, and this is obviously one of them.

The big question, then: should you shift to an M1 Mac? If you do simple edits or rely on modern codecs, you could have a really good experience. Essentially, if your main Mac is currently a low-end Mac, the new M1 Mac is likely to be better than it at everything.

But… if you work with more complex graphics, you might be better waiting for the new Mac with a more capable GPU to match the amazing CPU. Do get 16GB of RAM if you want to tackle more complex tasks. But probably the biggest issue is plug-in compatibility.

While FCP itself is working well on Apple silicon, many complex video and audio plug-ins are not, and it could be a little while before they’re ready. Adobe and Microsoft apps aren’t native yet either, so you won’t see a huge speed boost on those today.

In summary then, if you’re a professional relying on plug-ins, you can’t do your job yet. If you’re a Premiere or Resolve editor, you won’t see the same speed boost yet. So if you need to wait for software, maybe wait a little longer for an even better Mac?

The new Macs are great, but the next ones will be even better. If your workflow currently uses a lower-end Mac, #FCP and few plug-ins, you’ll be very happy with an M1 replacement, but many pro workflows can’t take advantage just yet. But the future is bright.

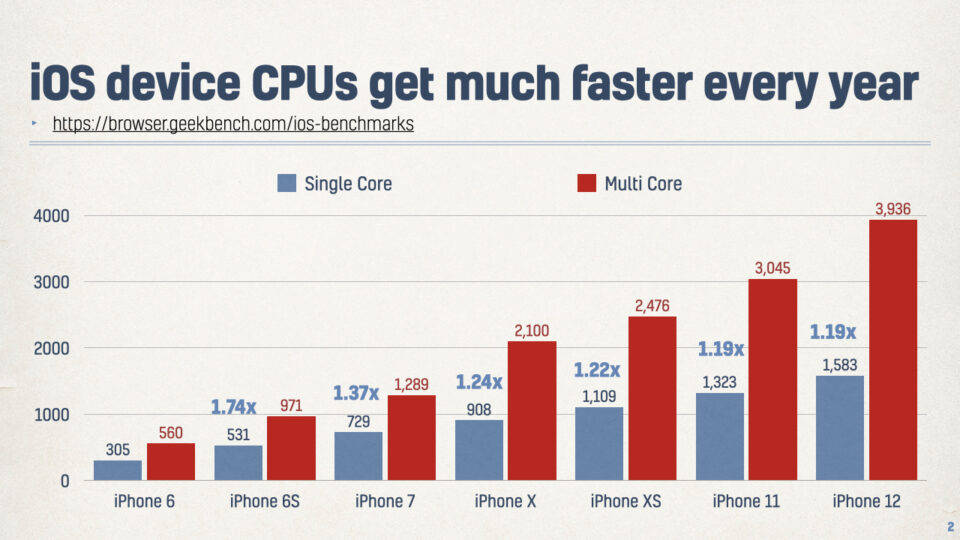

Looking forward, the current performance gap is only more striking when you look at how much faster iOS device CPUs have been getting:

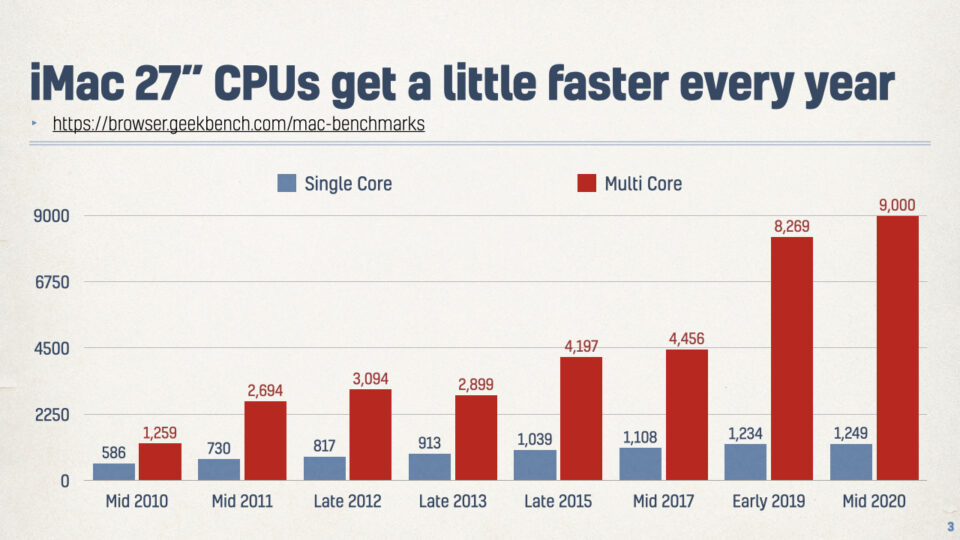

Especially when compared to Intel’s desktop/laptop CPUs (as used in the top-spec iMac each year) where the only real gains have been in multi-core performance:

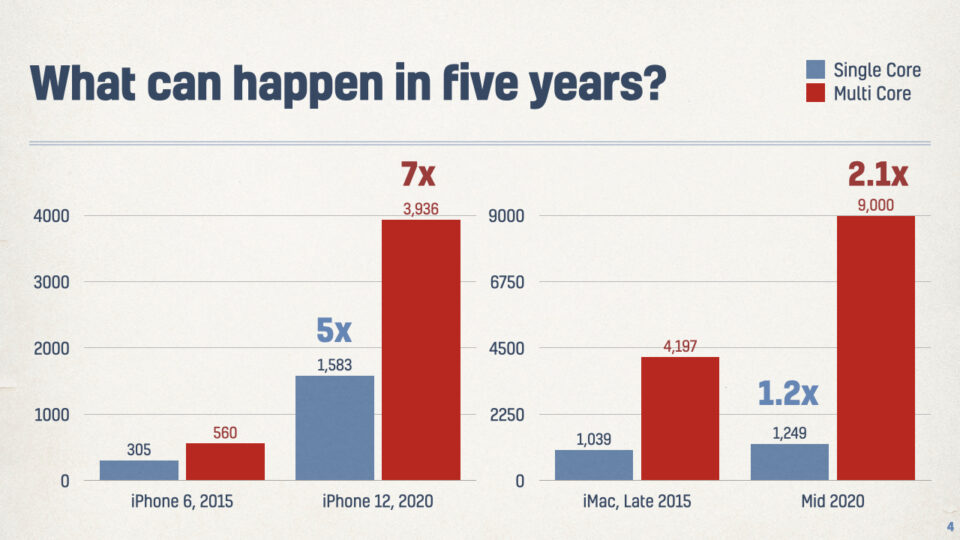

Add all that up, and over the past five years, the A-series chips have gotten 5x faster on single-core performance, and 7x faster on multi-core. Compare that to the chips in the best iMacs, which have only gotten 1.2x and 2.1x faster.

If Macs are potentially in line for 20% speed boosts every year, I’d certainly prefer to get a nice OLED TV as a monitor, and use a Mac mini Pro as my main Mac, swapping it out every year for a much faster model. But since the Mac mini Pro doesn’t exist, I’ll have to wait and see what Apple comes up with.

If their next MacBook Pro is as powerful as their new iMac, maybe I’ll go back to one Mac, connecting to more storage and bigger screens at home. If the iMac is the fastest option, then I’ll likely get one of those and a lower-end M1 laptop for on-set and training work. But that’s all theoretical.

For now, the low-end Mac line-up is an excellent choice for many people, even if it’s not perfect for post-production professionals just yet.

If you found that helpful, you might enjoy my new book, Final Cut Pro X: Efficient Editing, available now from Amazon, Packt, and others, in electronic or paper form. Use “25FCPX” to save 25% off at Amazon through the end of 2020. The X will be removed in the next edition, but little of the text changed.

There’s a free sample chapter and more info at fcpxefficientediting.com, where I will also host updates between versions.